Magrath Veterans stories

Most of these stories are extracted from:

“FLYING IN DARKNESS”. D BROOK HARKER. 2020. KEYLINE PUBLISHING, MAGRATH, ALBERTA

We would be happy to have other stories of Veterans who served our country

“FLYING IN DARKNESS”. D BROOK HARKER. 2020. KEYLINE PUBLISHING, MAGRATH, ALBERTA

We would be happy to have other stories of Veterans who served our country

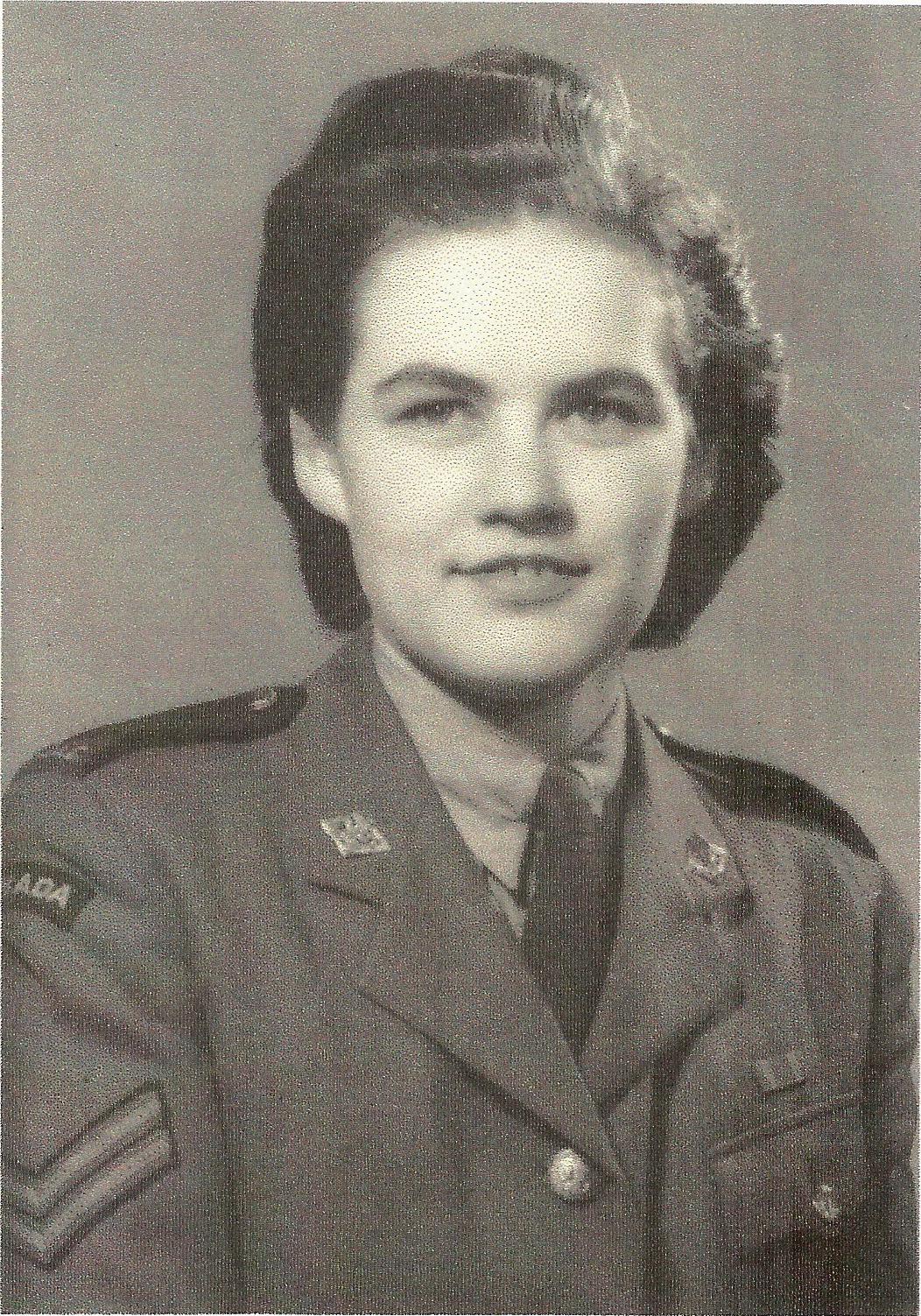

A. Louise Spencer

RCAF Women’s Division

Spit Upon

Corporal Ann Louise Spencer joined the RCAF Women’s Division (WD) in the summer of 1942, along with some 17,000 other women by the end of the war. Louise served in the Royal Canadian Air Force for the better part of four years. Her father, J. Arthur Spencer, having fought at Vimy Ridge during World War I, enlisted with the Calgary Highlanders during the Second World War, serving in Canada and Great Britain.

Initially posted to No. 8 Repair Depot in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Louise was shocked to find that the people of Winnipeg held little regard for women in the military. When she tried to get a seat in a partially filled restaurant, she was refused service and told that the facility was full. Another time she found herself spit upon while walking down the street. But according to her, conditions gradually improved after the YWCA printed a brief bio and picture of each of the girls in the local paper. Then people began inviting the women into their homes.

Louise later worked in the maintenance hangar at No. 19 SFTS (Service Flying Training School) in Vulcan, Alberta for two years. There, men were training for their pilot’s wings on the twin-engine Anson aircraft. Louise might have liked to fly, but quickly learned that the only women to do so in the war were those few who already held their pilot’s licenses—and then only to ferry planes to where they were needed by the men.

Louise Spencer and all those who served in the military deserve our gratitude. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such women and men did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

RCAF Women’s Division

Spit Upon

Corporal Ann Louise Spencer joined the RCAF Women’s Division (WD) in the summer of 1942, along with some 17,000 other women by the end of the war. Louise served in the Royal Canadian Air Force for the better part of four years. Her father, J. Arthur Spencer, having fought at Vimy Ridge during World War I, enlisted with the Calgary Highlanders during the Second World War, serving in Canada and Great Britain.

Initially posted to No. 8 Repair Depot in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Louise was shocked to find that the people of Winnipeg held little regard for women in the military. When she tried to get a seat in a partially filled restaurant, she was refused service and told that the facility was full. Another time she found herself spit upon while walking down the street. But according to her, conditions gradually improved after the YWCA printed a brief bio and picture of each of the girls in the local paper. Then people began inviting the women into their homes.

Louise later worked in the maintenance hangar at No. 19 SFTS (Service Flying Training School) in Vulcan, Alberta for two years. There, men were training for their pilot’s wings on the twin-engine Anson aircraft. Louise might have liked to fly, but quickly learned that the only women to do so in the war were those few who already held their pilot’s licenses—and then only to ferry planes to where they were needed by the men.

Louise Spencer and all those who served in the military deserve our gratitude. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such women and men did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Hans Pfeffel

POW

German Soldier

Hans Pfeffel was a German soldier captured at El Alamein in October 1942. He then got shipped to Canada via a circuitous route that included Egypt, South Africa, New York, and from thence across Canada by train to Lethbridge, arriving in February 1943.

The POW Internment Camp at Lethbridge (#133) was by far the largest Prisoner of War camp in Canada. The mile square complex was established in response to British concerns that, if invaded, prisoners of war in England could become a liability. The camp at Lethbridge housed almost half the prisoners in Canada. At one time as many as 17,000 POWs were in the camp—more prisoners than the population of the city of Lethbridge!

As the war turned badly for Germany, POWs in Canada stopped receiving pay support from home and were given the opportunity to work outside the compound to earn money for canteen extras. Pay was fifty cents a day. By 1944 more than 6,000 POWs worked outside the camp for a monthly turnover of $10,000. If they did not own a German uniform, prisoners wore a blue denim outfit having a big red circle on the back and a red stripe down the side. A standing joke amongst the inmates was that back in Germany, only officers got a red stripe down the side of their pants.

When the war began to wind down, some of the POWs expressed a desire to stay in Canada. They had heard of the devastation at home and many had no reason to return. But the Geneva Convention required that all prisoners of war be returned to their home country. The irony was that just as guards had been required on the trains to stop prisoners from escaping en route to the prison camps, now guards were required to stop them from jumping off and trying to remain in Canada.

Hans Pfeffel eventually returned to live in the area. A tailor by trade before the war, he established a laundry and dry-cleaning business in Magrath and went on to become President of the town’s Chamber of Commerce.

POW

German Soldier

Hans Pfeffel was a German soldier captured at El Alamein in October 1942. He then got shipped to Canada via a circuitous route that included Egypt, South Africa, New York, and from thence across Canada by train to Lethbridge, arriving in February 1943.

The POW Internment Camp at Lethbridge (#133) was by far the largest Prisoner of War camp in Canada. The mile square complex was established in response to British concerns that, if invaded, prisoners of war in England could become a liability. The camp at Lethbridge housed almost half the prisoners in Canada. At one time as many as 17,000 POWs were in the camp—more prisoners than the population of the city of Lethbridge!

As the war turned badly for Germany, POWs in Canada stopped receiving pay support from home and were given the opportunity to work outside the compound to earn money for canteen extras. Pay was fifty cents a day. By 1944 more than 6,000 POWs worked outside the camp for a monthly turnover of $10,000. If they did not own a German uniform, prisoners wore a blue denim outfit having a big red circle on the back and a red stripe down the side. A standing joke amongst the inmates was that back in Germany, only officers got a red stripe down the side of their pants.

When the war began to wind down, some of the POWs expressed a desire to stay in Canada. They had heard of the devastation at home and many had no reason to return. But the Geneva Convention required that all prisoners of war be returned to their home country. The irony was that just as guards had been required on the trains to stop prisoners from escaping en route to the prison camps, now guards were required to stop them from jumping off and trying to remain in Canada.

Hans Pfeffel eventually returned to live in the area. A tailor by trade before the war, he established a laundry and dry-cleaning business in Magrath and went on to become President of the town’s Chamber of Commerce.

Bob Rainbow

‘Claimed –Back’

Signal Corps

Bob Rainbow of Magrath, Alberta was posted to the Signal Corp in Italy. His younger brother Jack Rainbow, also in the Signal Corp, said it was Bob who saved him from being transferred to the infantry.

There was a regulation that allowed a brother to claim his junior brother back into the Corps. And when the infantry threatened to absorb Jack, Bob claimed his younger brother back into the Corps.

The two brothers only saw each other once during their time overseas.

Bob Rainbow and all those who served in the military deserve our gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

‘Claimed –Back’

Signal Corps

Bob Rainbow of Magrath, Alberta was posted to the Signal Corp in Italy. His younger brother Jack Rainbow, also in the Signal Corp, said it was Bob who saved him from being transferred to the infantry.

There was a regulation that allowed a brother to claim his junior brother back into the Corps. And when the infantry threatened to absorb Jack, Bob claimed his younger brother back into the Corps.

The two brothers only saw each other once during their time overseas.

Bob Rainbow and all those who served in the military deserve our gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Arnold Ririe DFC

Mid-Upper Gunner

405 Eagle Sdn

Arnold Ririe DFC of Magrath was a Mid-Upper Gunner aboard an old Halifax bomber. He operated a gun turret on the top of the fuselage, his position being regarded as the primary observer, “responsible for detecting the approach of enemy fighter aircraft as well preventing collisions with friendly aircraft and accidental mid-air bomb strikes.”

Ririe started out with 433 RCAF Squadron, flying into France and the heavily defended Ruhr valley of Germany. After 18 trips his crew was recommended for reassignment to 405 Eagle Squadron, part of No. 8 Pathfinder Group. As Pathfinders, they did not carry bombs, he said, “just went in packing flares.” On their thirteenth trip, trouble found them.

“We got into the target a bit late,” said Ririe, “and [the enemy] had us targeted with a lot of flak. We dropped our flares and were on the way home when the flak got us.” The pilot was fatally wounded, the aircraft lost altitude and the tail gunner bailed out in the confusion. According to Ririe, the second navigator, took over the controls but was by no means an experienced flier. “We were lucky that night;” he said, “there were no fighters after us.”

They arrived over England about 2 o’clock in the morning, “but so far behind the main force,” said Ririe, “they had shut the landing lights off on the dromes.” An American squadron heard their Mayday and turned on its landing lights. The crippled bomber came in 500 feet too high and was told to go around again. They never made it, belly-landing in a field a couple of miles past the aerodrome—because there was no fuel to go around again! For their heroism, the rest of the crew received Distinguished Flying Medals (DFMs) and Ririe, commissioned by then, received a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

Soon crewed-up again, he went on to fly another 23 ops in the Master Bomber of his Pathfinder Group. The Master Bomber was equipped with special high-frequency radio equipment that allowed it to communicate with overhead aircraft in a raid. It first directed the pre-bomb Pathfinder Force to mark the target area with coloured flares then remained behind to tell the overhead attacking bombers where to drop their payload in relation to the flares.

Arnold Ririe and all those who entered the Service during World War II deserve our gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Mid-Upper Gunner

405 Eagle Sdn

Arnold Ririe DFC of Magrath was a Mid-Upper Gunner aboard an old Halifax bomber. He operated a gun turret on the top of the fuselage, his position being regarded as the primary observer, “responsible for detecting the approach of enemy fighter aircraft as well preventing collisions with friendly aircraft and accidental mid-air bomb strikes.”

Ririe started out with 433 RCAF Squadron, flying into France and the heavily defended Ruhr valley of Germany. After 18 trips his crew was recommended for reassignment to 405 Eagle Squadron, part of No. 8 Pathfinder Group. As Pathfinders, they did not carry bombs, he said, “just went in packing flares.” On their thirteenth trip, trouble found them.

“We got into the target a bit late,” said Ririe, “and [the enemy] had us targeted with a lot of flak. We dropped our flares and were on the way home when the flak got us.” The pilot was fatally wounded, the aircraft lost altitude and the tail gunner bailed out in the confusion. According to Ririe, the second navigator, took over the controls but was by no means an experienced flier. “We were lucky that night;” he said, “there were no fighters after us.”

They arrived over England about 2 o’clock in the morning, “but so far behind the main force,” said Ririe, “they had shut the landing lights off on the dromes.” An American squadron heard their Mayday and turned on its landing lights. The crippled bomber came in 500 feet too high and was told to go around again. They never made it, belly-landing in a field a couple of miles past the aerodrome—because there was no fuel to go around again! For their heroism, the rest of the crew received Distinguished Flying Medals (DFMs) and Ririe, commissioned by then, received a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

Soon crewed-up again, he went on to fly another 23 ops in the Master Bomber of his Pathfinder Group. The Master Bomber was equipped with special high-frequency radio equipment that allowed it to communicate with overhead aircraft in a raid. It first directed the pre-bomb Pathfinder Force to mark the target area with coloured flares then remained behind to tell the overhead attacking bombers where to drop their payload in relation to the flares.

Arnold Ririe and all those who entered the Service during World War II deserve our gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Lewis (Steve) Stevenson

Lead Cook

HMCS Woodstock

Lewis ‘Steve’ Stevenson of Magrath spent his entire war years patrolling the west coast of Canada. According to his wife, Alice Carmichael, Steve joined the navy in 1942 as a cook, “because he liked to cook for his mother.” But he surely must have anticipated a difference of scale in the task that lay ahead. The fact is, said Alice, that Steve trained for five or six months in Quebec to cook for groups of from 100 to 300 men. In Halifax, he boarded the corvette HMCS Woodstock as its Lead Cook, and as an officer. From there he sailed down the American coast and through the Panama Canal into the Pacific.

Although Steve was trained to operate Old Howie, the corvette’s lone Howitzer, he did not need to draw upon that skill during his sole attack upon the enemy. He was working short-handed in the galley and a fellow shipmate periodically poked his head in to irritatingly ask, “How’s it going cookie?” The fellow knew that Steve did not like to be called cookie. The overworked chef ignored his persecutor for some time, noting abstractly where an empty pop bottle stood on the counter, close at hand. When the sailor yet again stuck his head into the galley, without looking Steve flung the bottle in his direction. It was a lucky shot—he hit the sailor smack in the head and the targeted fellow dropped like a stone!

Steve was called up on report before a ship’s inquiry. Each of the combatants was separately summoned to tell his story then the two of them were brought together for a final verdict. According to Alice, “Steve didn’t know whether he was going to have to walk the plank or what.” As it turned out, the brass admitted that he had been under a lot of pressure and promised to get him more help. Meanwhile, Steve was cautioned to tame his temper.

Lewis Stevenson was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Lead Cook

HMCS Woodstock

Lewis ‘Steve’ Stevenson of Magrath spent his entire war years patrolling the west coast of Canada. According to his wife, Alice Carmichael, Steve joined the navy in 1942 as a cook, “because he liked to cook for his mother.” But he surely must have anticipated a difference of scale in the task that lay ahead. The fact is, said Alice, that Steve trained for five or six months in Quebec to cook for groups of from 100 to 300 men. In Halifax, he boarded the corvette HMCS Woodstock as its Lead Cook, and as an officer. From there he sailed down the American coast and through the Panama Canal into the Pacific.

Although Steve was trained to operate Old Howie, the corvette’s lone Howitzer, he did not need to draw upon that skill during his sole attack upon the enemy. He was working short-handed in the galley and a fellow shipmate periodically poked his head in to irritatingly ask, “How’s it going cookie?” The fellow knew that Steve did not like to be called cookie. The overworked chef ignored his persecutor for some time, noting abstractly where an empty pop bottle stood on the counter, close at hand. When the sailor yet again stuck his head into the galley, without looking Steve flung the bottle in his direction. It was a lucky shot—he hit the sailor smack in the head and the targeted fellow dropped like a stone!

Steve was called up on report before a ship’s inquiry. Each of the combatants was separately summoned to tell his story then the two of them were brought together for a final verdict. According to Alice, “Steve didn’t know whether he was going to have to walk the plank or what.” As it turned out, the brass admitted that he had been under a lot of pressure and promised to get him more help. Meanwhile, Steve was cautioned to tame his temper.

Lewis Stevenson was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Rulon Thomson

Link Trainer

RCAF

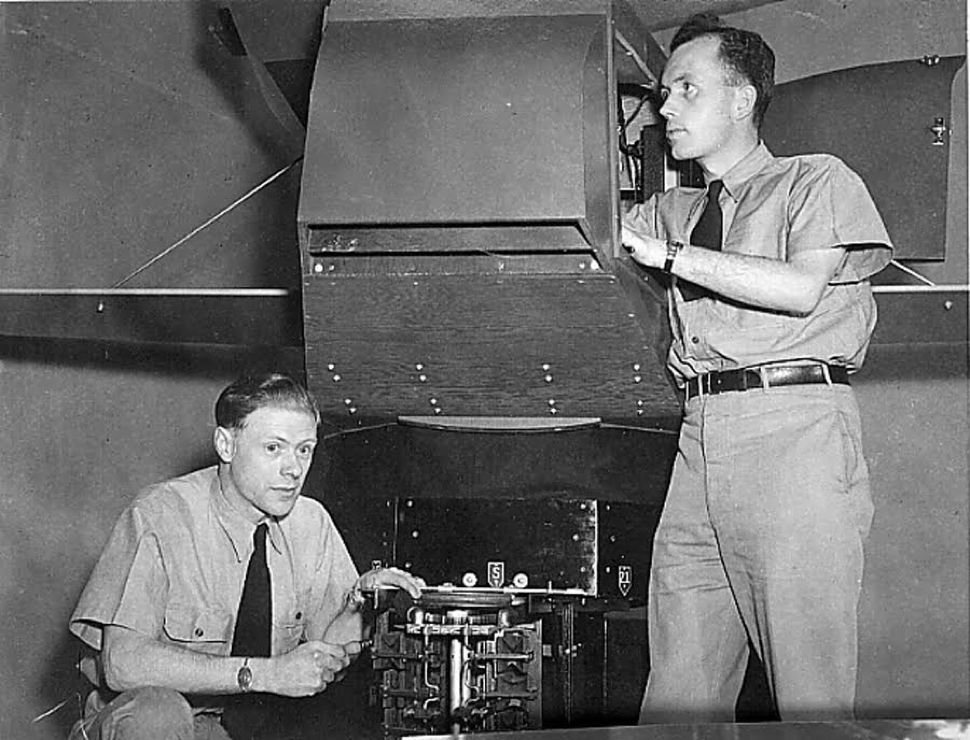

Rulon Thomson of Magrath was responsible for calibrating and maintaining the ground-based Link Trainer on base in Calgary, Alberta and in Abbotsford, B.C. The Link foreshadowed the modern flight simulator as a way to teach pilots to fly and was used into the 1960's. It constituted a cramped little cockpit that might be one of twelve or so housed within a given training area.

In order to navigate this pseudo aircraft, student pilots tried to hone in on a set of radio signals. A duplicate set of instruments and controls allowed an instructor to monitor their every move at a nearby desk. The resulting “flight path” was systematically plotted on paper by a small three-wheeled mechanical device called a crab.

The Link trainer could had extremely sensitive controls and poor performance on it could jeopardize your career as a pilot. Hence, a fellow who did not do well on the Link, might be tempted to criticize the accuracy of the machine. Such a complaint was logged when Rulon was on duty. In Rulon’s defence, the brass brought in a high-ranking officer to fly the thing, who declared it to be fully reliable and accurate. That put an end to flier complaints.

Rulon Thomson and all those who served in the military deserve our admiration. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Link Trainer

RCAF

Rulon Thomson of Magrath was responsible for calibrating and maintaining the ground-based Link Trainer on base in Calgary, Alberta and in Abbotsford, B.C. The Link foreshadowed the modern flight simulator as a way to teach pilots to fly and was used into the 1960's. It constituted a cramped little cockpit that might be one of twelve or so housed within a given training area.

In order to navigate this pseudo aircraft, student pilots tried to hone in on a set of radio signals. A duplicate set of instruments and controls allowed an instructor to monitor their every move at a nearby desk. The resulting “flight path” was systematically plotted on paper by a small three-wheeled mechanical device called a crab.

The Link trainer could had extremely sensitive controls and poor performance on it could jeopardize your career as a pilot. Hence, a fellow who did not do well on the Link, might be tempted to criticize the accuracy of the machine. Such a complaint was logged when Rulon was on duty. In Rulon’s defence, the brass brought in a high-ranking officer to fly the thing, who declared it to be fully reliable and accurate. That put an end to flier complaints.

Rulon Thomson and all those who served in the military deserve our admiration. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Darl Turner

Another man’s gloves

Reconnaissance

09 Nov 2020

Darl (DAHR-l] Turner of Magrath was killed while flying a reconnaissance mission over Norway. He departed Wick, Scotland on December 8, 1943, flying in a Beaufighter, headed for Sognefjord and the Bremanger area. Yet when no further news was received from Darl’s plane, the Air Force presumed him to have been shot down by flak. However, some time passed away before the crashed aircraft and the bodies of its two airmen were verified as recovered in Norway. Even then, considerable confusion arose as to whether Darl was one of the dead, because he was wearing a pair of borrowed flying gloves bearing another man’s initials. Darl had been with 404 RCAF Squadron less than three months.

Back in Magrath, Darl’s parents received an unusually long, 5-page letter of condolence from his “squadron commander and personal friend”, W/C C.A. Wallis. Wallis described their son as “a good operational pilot with considerably more flying time than that of his comrades because of his [prior] instructional tour [in Canada].” But Darl’s depth of flying experience, noted Wallis, might have been his Achilles heel wherein “He was a keen pilot and may have come a little too close....”

Darl Turner was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

George Turner

Ack-Ack Gunner

Letter-Writer

George Turner joined the Royal Canadian Army in the fall of 1940. He was 31 years of age, married, with two pre-teenage children. Stationed at an Army base near London. George regularly visited his wife’s British cousin, Trixie Wisdom. Together with her husband, Harry, she lived in the little town of Berrylands, with her younger cousin, Marjorie. George found himself taken in by Trixie’s good nature, hospitality and home cooking. In Trixie, he saw his wife Thelma’s kindred spirit.

In April 1942, Blair Harker, George and Thelma’s good friend, was posted to the RCAF in England. Thereafter, George and Blair spent much of their free time together. George sent regular letters home to his wife. In later years, their daughter, Janet T. Alston, carefully transcribed 70 of these letters into type-written text.

George was stationed at Bexhill, on the coast about 50mi SE of London where he operated an ack-ack gun in the 17th Light Aircraft Battery. One night when George and his buddies were on the town, they ran into Sir John Neagle, “a real English gentleman.” Sir John became offended when his guests offered to pay for their own drinks, covering the costs of the entire evening himself. A semi-retired surgeon having a Ford V-8 and a chauffeur, he toured the soldiers about. They saw where Sir John lived but none of them had a clue as to how to return.

In early August, George moved to Farnborough, the all-Canadian camp about 30mi out of London. He was enrolled in a three-month Signals School, where he hoped to increase his education and get a raise in pay. But as George wrote to Thelma, “This going to school again at my age [33] is not what it is cracked up to be. I don’t learn things as easy as I should.” Meanwhile, the ill-fated Dieppe Raid had taken place and because George was in Signals School, he felt fortunate not to have been involved.

By late November, at Bognor Regis on the English Channel, George’s base was bombed by two lone enemy aircraft. He stuck his head out the window, “just as the bombs went off.” It was nasty weather with low clouds and the planes had sneaked in. One got shot down by a local Limey ack-ack gun and the London papers reported a fighter had done it. “There was not a fighter in sight!” George decried. “One of our guns hit [the plane]… and it crashed into the sea.”

Early the following year, George, now in Bramshott near London, was just getting out of the hospital with undiagnosed stomach problems. He thought it likely he would be sent back to the 17th Battery and was trying to wangle a trip back to Canada as a personnel escort. But most of the men who did so, were Category ‘C2’ and he was Category ‘A’. George was tired of army life and the inept way things were run. He expressed the hope that after the war, many wrongs would be brought to light through a forced reckoning of commissioned officers and NCOs.

One time when on leave, George and Trixie attended a movie in nearby Surbiton--when the city was bombed. Inside the theatre, the air raid had been hardly audible but a notice flashed on the screen when the sirens went off. Trixie thought they ought to go right home because Marjorie was there alone, but George dissuaded her until the raid was about ended. “I did not think I should take her out,” he later wrote to Thelma, “as the gunfire was very heavy.” The gunfire, he said, “is a lot worse than bombs.” At home, they found a clearly frightened Marjorie.

Talk was circulating around camp about George’s unit being posted to the Continent. He felt he had spent his last leave in England and would soon be moving out. But George tried to assure Thelma that it was nothing to worry about. “It has had to come sometime,” he said, “and the sooner we go there the sooner it will be over with.”

Meanwhile, in late March, he came to learn that Blair Harker was now flying Intruder missions into occupied France. George arrived in Berrylands to find that Blair, still stationed 200 miles north, had been there the night before. From Trixie, George discovered that “he is down on some hush-hush stuff and could not tell them anything about it.”

A month later, on the evening of April 17, George was again in Berrylands, when Blair walked in. Soon, all of their friends were together. Blair could not tell them why he was in the area. “Some secret work,” noted George in a letter home. “I sure hope he gets through okay.”

And then Blair was gone, never to return.

George Turner survived the war. He and all those who served in the military deserve our never-ending gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Ack-Ack Gunner

Letter-Writer

George Turner joined the Royal Canadian Army in the fall of 1940. He was 31 years of age, married, with two pre-teenage children. Stationed at an Army base near London. George regularly visited his wife’s British cousin, Trixie Wisdom. Together with her husband, Harry, she lived in the little town of Berrylands, with her younger cousin, Marjorie. George found himself taken in by Trixie’s good nature, hospitality and home cooking. In Trixie, he saw his wife Thelma’s kindred spirit.

In April 1942, Blair Harker, George and Thelma’s good friend, was posted to the RCAF in England. Thereafter, George and Blair spent much of their free time together. George sent regular letters home to his wife. In later years, their daughter, Janet T. Alston, carefully transcribed 70 of these letters into type-written text.

George was stationed at Bexhill, on the coast about 50mi SE of London where he operated an ack-ack gun in the 17th Light Aircraft Battery. One night when George and his buddies were on the town, they ran into Sir John Neagle, “a real English gentleman.” Sir John became offended when his guests offered to pay for their own drinks, covering the costs of the entire evening himself. A semi-retired surgeon having a Ford V-8 and a chauffeur, he toured the soldiers about. They saw where Sir John lived but none of them had a clue as to how to return.

In early August, George moved to Farnborough, the all-Canadian camp about 30mi out of London. He was enrolled in a three-month Signals School, where he hoped to increase his education and get a raise in pay. But as George wrote to Thelma, “This going to school again at my age [33] is not what it is cracked up to be. I don’t learn things as easy as I should.” Meanwhile, the ill-fated Dieppe Raid had taken place and because George was in Signals School, he felt fortunate not to have been involved.

By late November, at Bognor Regis on the English Channel, George’s base was bombed by two lone enemy aircraft. He stuck his head out the window, “just as the bombs went off.” It was nasty weather with low clouds and the planes had sneaked in. One got shot down by a local Limey ack-ack gun and the London papers reported a fighter had done it. “There was not a fighter in sight!” George decried. “One of our guns hit [the plane]… and it crashed into the sea.”

Early the following year, George, now in Bramshott near London, was just getting out of the hospital with undiagnosed stomach problems. He thought it likely he would be sent back to the 17th Battery and was trying to wangle a trip back to Canada as a personnel escort. But most of the men who did so, were Category ‘C2’ and he was Category ‘A’. George was tired of army life and the inept way things were run. He expressed the hope that after the war, many wrongs would be brought to light through a forced reckoning of commissioned officers and NCOs.

One time when on leave, George and Trixie attended a movie in nearby Surbiton--when the city was bombed. Inside the theatre, the air raid had been hardly audible but a notice flashed on the screen when the sirens went off. Trixie thought they ought to go right home because Marjorie was there alone, but George dissuaded her until the raid was about ended. “I did not think I should take her out,” he later wrote to Thelma, “as the gunfire was very heavy.” The gunfire, he said, “is a lot worse than bombs.” At home, they found a clearly frightened Marjorie.

Talk was circulating around camp about George’s unit being posted to the Continent. He felt he had spent his last leave in England and would soon be moving out. But George tried to assure Thelma that it was nothing to worry about. “It has had to come sometime,” he said, “and the sooner we go there the sooner it will be over with.”

Meanwhile, in late March, he came to learn that Blair Harker was now flying Intruder missions into occupied France. George arrived in Berrylands to find that Blair, still stationed 200 miles north, had been there the night before. From Trixie, George discovered that “he is down on some hush-hush stuff and could not tell them anything about it.”

A month later, on the evening of April 17, George was again in Berrylands, when Blair walked in. Soon, all of their friends were together. Blair could not tell them why he was in the area. “Some secret work,” noted George in a letter home. “I sure hope he gets through okay.”

And then Blair was gone, never to return.

George Turner survived the war. He and all those who served in the military deserve our never-ending gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Grant Stevenson

Too good at navigation

Whitley Bomber A/C

Grant Stevenson was just beginning his service in the Air Force, stationed at Brandon, Manitoba in December 1941. As an eighteen-year-old, a lot of the fellows there were senior to him, many of whom he perceived to be, “trying to get involved in something shady....” Being a teetotaller and hailing from a dry Church town, it seemed to him that “there was a lot of drinking going on.”

As his training progressed, Grant found himself gaining experience at ‘flying’ the ground-based Link trainer, a precursor to the modern Flight Simulator. The devise could mimic climbs, dives and even spins, yet had extremely sensitive controls—and poor performance on it could end your career as a pilot before it ever started. At first, Grant did not do so well on the Link. “As they recorded my flight,” he chuckled, “technically I was flying underground!”

Eventually, Grant washed out of flying and could not understand why. That is, not until he and two other fellows on the train to navigator school got comparing their grades. The three of them had the highest marks in their class! They were simply too good at navigation to be allowed to generalize as pilots.

When it came time for Grant to head overseas from Halifax, he marched down to the docks—and boarded a train. His route lay through New York City where he took a tour of Times Square, then sailed aboard the Queen Elizabeth. According to Grant, the convoy that left Halifax about the same time as his left New York, was torpedoed!

Grant arrived in England during the spring of 1943 where he awaited processing in the seaside resort town of Bournemouth, staying at the Carleton Hotel. One Sunday afternoon a roommate came running down from the rooftop hollering, “The German’s are bombing us!” Grant threw open the window just in time to catch a glimpse of the enemy aircraft wave hopping (flying low, to avoid radar) on their way out to sea. It was his first exposure to the enemy.

As a navigator, job function demanded that Grant determine the proper aircraft heading under any condition, whether in enemy skies or at home. But getting the pilot of the plane to follow his directives could be quite another thing. One night, Grant was navigating aboard their twin-engine Whitley as the medium-range bomber returned home, flying over the English Chanel towards southern England. Early in their return flight, he passed the plane’s RAF pilot a note, advising him to alter course and turn due north, so as to fly directly inland. But, noted Grant of this particular Flight Lieutenant, “he didn’t take instruction well.”

Sometime later, upon glancing out the window, Grant became alarmed to see that their bomber was advancing on a series of ground fires and searchlights in the distance. When he asked the pilot what course they were on, he was told they were still heading northwest—now directly into the flak over the city of Bristol, on the far side of England! Grant later learned that the fellow had been letting a friend fly the aircraft, and the two of them had traded seats just as he had passed the note over. Grant quickly gave the pilot a new pundit course to steer by, narrowly avoiding disaster.

Grant Stevenson went on to survive the war. He was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a tale of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Too good at navigation

Whitley Bomber A/C

Grant Stevenson was just beginning his service in the Air Force, stationed at Brandon, Manitoba in December 1941. As an eighteen-year-old, a lot of the fellows there were senior to him, many of whom he perceived to be, “trying to get involved in something shady....” Being a teetotaller and hailing from a dry Church town, it seemed to him that “there was a lot of drinking going on.”

As his training progressed, Grant found himself gaining experience at ‘flying’ the ground-based Link trainer, a precursor to the modern Flight Simulator. The devise could mimic climbs, dives and even spins, yet had extremely sensitive controls—and poor performance on it could end your career as a pilot before it ever started. At first, Grant did not do so well on the Link. “As they recorded my flight,” he chuckled, “technically I was flying underground!”

Eventually, Grant washed out of flying and could not understand why. That is, not until he and two other fellows on the train to navigator school got comparing their grades. The three of them had the highest marks in their class! They were simply too good at navigation to be allowed to generalize as pilots.

When it came time for Grant to head overseas from Halifax, he marched down to the docks—and boarded a train. His route lay through New York City where he took a tour of Times Square, then sailed aboard the Queen Elizabeth. According to Grant, the convoy that left Halifax about the same time as his left New York, was torpedoed!

Grant arrived in England during the spring of 1943 where he awaited processing in the seaside resort town of Bournemouth, staying at the Carleton Hotel. One Sunday afternoon a roommate came running down from the rooftop hollering, “The German’s are bombing us!” Grant threw open the window just in time to catch a glimpse of the enemy aircraft wave hopping (flying low, to avoid radar) on their way out to sea. It was his first exposure to the enemy.

As a navigator, job function demanded that Grant determine the proper aircraft heading under any condition, whether in enemy skies or at home. But getting the pilot of the plane to follow his directives could be quite another thing. One night, Grant was navigating aboard their twin-engine Whitley as the medium-range bomber returned home, flying over the English Chanel towards southern England. Early in their return flight, he passed the plane’s RAF pilot a note, advising him to alter course and turn due north, so as to fly directly inland. But, noted Grant of this particular Flight Lieutenant, “he didn’t take instruction well.”

Sometime later, upon glancing out the window, Grant became alarmed to see that their bomber was advancing on a series of ground fires and searchlights in the distance. When he asked the pilot what course they were on, he was told they were still heading northwest—now directly into the flak over the city of Bristol, on the far side of England! Grant later learned that the fellow had been letting a friend fly the aircraft, and the two of them had traded seats just as he had passed the note over. Grant quickly gave the pilot a new pundit course to steer by, narrowly avoiding disaster.

Grant Stevenson went on to survive the war. He was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a tale of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Jack Harker

Corkscrew-right!

Bomber Pilot

Jack Harker was a bomber pilot, flying a Halifax out of Eastmore, Yorkshire. He arrived in England in February 1944, eventually posted to 415 RCAF Squadron. Some say that the Air Force was very particular as to how they selected which pilots flew what aircraft. That may have been so, said Jack, but “one day the Air Force was looking for five bomber pilots. They came into the room and five of us were there, and they took us all.”

It took quite an organization to feed and take care of the 13,000 men he sailed with on convoy across the North Atlantic. You only ate two times a day, recalled Jack, twelve hours apart. If you drew the 2 PM slot then you ate again at 2 AM, or not at all. As a flier used to motion sickness, Jack could cope with the roll of the sea, and as an officer he was assigned to one of the upper decks with fresh air and space to move around. But on the lower decks amongst the enlisted men, said Jack, “the place was stinking from the vomit.”

As a young man from the Colonies, in England Jack ran into plenty of so-called superior British types. “There were a lot of difficult RAF officers,” he said, “riff-RAFs we called them. If you couldn’t memorize the pundit codes [lights flashed from Morse code signal beacons] for the area you were in… they’d make you walk around the perimeter track with your seat parachute strapped on.” According to him, “It felt like being kicked in the seat of the pants every step you took.” Still, Jack admitted, “such penalties did promote learning your pundit signals.”

Once a novice flier got very far from base, he often had no idea where he was in the sky and had to call in for a homing vector. Jack confessed that he never would admit when he got lost. He called in to get a heading on a homing beacon as though he was flying a routine practice circuit. The individual controller’s ranges were so limited, he said, they knew about where you were and once you had the heading, you found your own way home. Jack’s calmly worded request went something like this, “Hello Darkie, this is Broomstick Yellow Two One [21], request practice QDM [radio bearing].” It worked every time!

When on military leave in London, Jack preferred to stay at the Strand Palace in the heart of the city. He remembered the dance hall at the Royal Opera House, in Covent Garden—a huge place accommodating 1500 Jitterbugging people, perhaps operating around the clock. “It was a 24-hour dance hall as far as I knew,” said Jack. “They didn’t even stop to change the orchestra. [The band] played on a rotating stage and the next time you looked up, the stage had moved, and another band was playing.”

Jack and his aircrew of 6 others flew both day and night missions deep into Germany. He acknowledged that the feelings related to those separate flights are “impossible to describe,” involving places like Hamburg, Kiel and the Ruhr Valley

On bombing runs, despite the aid of the indicator flares laid down by the advance Pathfinder squadrons, bombing was by no means a precision exercise. During practice, Jack’s bomb aimer had been congratulated for their accuracy—but it was much harder to be precise over a real target. There, the Master Bomber would fly below, trying to correct for inaccurate flares by telling the overhead planes to “bomb to the left,” or “bomb behind the green.” As it was, said Jack, “we could really only do our best to scatter the bombs as close as possible….”

One night, the weather was duff and bomber flying was called off. If you had flown that night, you were not required to show up at morning parade. Jack and his companions figured no one knew they had not flown and skipped morning parade. But the ruse failed, and they were severely penalized, “required to report to the Orderly Officer every day for two weeks, from 6 AM to midnight, every hour on the hour!” Jack tried sending in one of his men to sign for the lot. Not sufficient! “You can’t do this to an officer,” he complained to the Sergeant Major. “I know you can’t,” the fellow replied, “anywhere but here.” It was a long two weeks.

Nightfighters were an ever-present threat. In attempting to escape one, a bomber could initiate a violent evasive manoeuvre called a corkscrew. This consisted of quickly rolling the aircraft up onto one side, then dropping back and rolling it up onto the other. The corkscrew was less radical than an outright dive because “the partial roll kept a positive G-force on the aircraft, so every one stayed in their seats….”

Jack only had to corkscrew once on a run. He put the plane on its side and did a single, half corkscrew—enough to lose the nightfighter. “I knew we were near the bottom of the Pack,” he said. “If we had been higher up, I doubt if I had done it, the risk of collision with another aircraft was too great.

Jack Harker returned home after the war. He and all those who served deserve our never-ending gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Corkscrew-right!

Bomber Pilot

Jack Harker was a bomber pilot, flying a Halifax out of Eastmore, Yorkshire. He arrived in England in February 1944, eventually posted to 415 RCAF Squadron. Some say that the Air Force was very particular as to how they selected which pilots flew what aircraft. That may have been so, said Jack, but “one day the Air Force was looking for five bomber pilots. They came into the room and five of us were there, and they took us all.”

It took quite an organization to feed and take care of the 13,000 men he sailed with on convoy across the North Atlantic. You only ate two times a day, recalled Jack, twelve hours apart. If you drew the 2 PM slot then you ate again at 2 AM, or not at all. As a flier used to motion sickness, Jack could cope with the roll of the sea, and as an officer he was assigned to one of the upper decks with fresh air and space to move around. But on the lower decks amongst the enlisted men, said Jack, “the place was stinking from the vomit.”

As a young man from the Colonies, in England Jack ran into plenty of so-called superior British types. “There were a lot of difficult RAF officers,” he said, “riff-RAFs we called them. If you couldn’t memorize the pundit codes [lights flashed from Morse code signal beacons] for the area you were in… they’d make you walk around the perimeter track with your seat parachute strapped on.” According to him, “It felt like being kicked in the seat of the pants every step you took.” Still, Jack admitted, “such penalties did promote learning your pundit signals.”

Once a novice flier got very far from base, he often had no idea where he was in the sky and had to call in for a homing vector. Jack confessed that he never would admit when he got lost. He called in to get a heading on a homing beacon as though he was flying a routine practice circuit. The individual controller’s ranges were so limited, he said, they knew about where you were and once you had the heading, you found your own way home. Jack’s calmly worded request went something like this, “Hello Darkie, this is Broomstick Yellow Two One [21], request practice QDM [radio bearing].” It worked every time!

When on military leave in London, Jack preferred to stay at the Strand Palace in the heart of the city. He remembered the dance hall at the Royal Opera House, in Covent Garden—a huge place accommodating 1500 Jitterbugging people, perhaps operating around the clock. “It was a 24-hour dance hall as far as I knew,” said Jack. “They didn’t even stop to change the orchestra. [The band] played on a rotating stage and the next time you looked up, the stage had moved, and another band was playing.”

Jack and his aircrew of 6 others flew both day and night missions deep into Germany. He acknowledged that the feelings related to those separate flights are “impossible to describe,” involving places like Hamburg, Kiel and the Ruhr Valley

On bombing runs, despite the aid of the indicator flares laid down by the advance Pathfinder squadrons, bombing was by no means a precision exercise. During practice, Jack’s bomb aimer had been congratulated for their accuracy—but it was much harder to be precise over a real target. There, the Master Bomber would fly below, trying to correct for inaccurate flares by telling the overhead planes to “bomb to the left,” or “bomb behind the green.” As it was, said Jack, “we could really only do our best to scatter the bombs as close as possible….”

One night, the weather was duff and bomber flying was called off. If you had flown that night, you were not required to show up at morning parade. Jack and his companions figured no one knew they had not flown and skipped morning parade. But the ruse failed, and they were severely penalized, “required to report to the Orderly Officer every day for two weeks, from 6 AM to midnight, every hour on the hour!” Jack tried sending in one of his men to sign for the lot. Not sufficient! “You can’t do this to an officer,” he complained to the Sergeant Major. “I know you can’t,” the fellow replied, “anywhere but here.” It was a long two weeks.

Nightfighters were an ever-present threat. In attempting to escape one, a bomber could initiate a violent evasive manoeuvre called a corkscrew. This consisted of quickly rolling the aircraft up onto one side, then dropping back and rolling it up onto the other. The corkscrew was less radical than an outright dive because “the partial roll kept a positive G-force on the aircraft, so every one stayed in their seats….”

Jack only had to corkscrew once on a run. He put the plane on its side and did a single, half corkscrew—enough to lose the nightfighter. “I knew we were near the bottom of the Pack,” he said. “If we had been higher up, I doubt if I had done it, the risk of collision with another aircraft was too great.

Jack Harker returned home after the war. He and all those who served deserve our never-ending gratitude. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

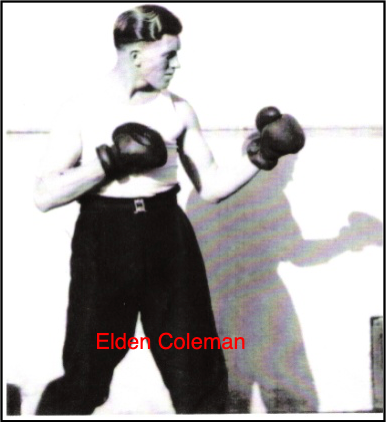

Elden Coleman

Swinging the Lead

P/T Instructor

Elden Coleman was a physical training (P/T) instructor in the Royal Canadian Army. On base at Cove, west of Farnborough, England, he and five other instructors worked their men hard amidst extensive training facilities that included two full gymnasiums. The main idea, said Elden, centred on keeping the fellows fit for combat. “We put ‘em in shape to go into battle,” he said, “and the demands of battle were supposed to be rigorous enough to keep them in shape.” Enlisted men were encouraged to participate in extra-curricular activities like basketball, football, track and field.

But P/T provided another valuable service—a form of discipline—to deter those fellows who were just “swinging the lead,” that is, not wanting to fully participate in physical exercises.

According to Elden, a typical P/T class involved hard training for fifty minutes out of an hour, with a ten-minute break before moving on to the next class. The fatigued men looked forward to the break. But in a group of thirty to forty men, he said, “you might have two or three guys who did not want to do anything, who were just swinging the lead.” As a punishment, Elden would announce that the whole class was going to continue exercising for the full hour, that there would be no ten-minute break before their next training session.

By the end of such a prolonged workout, he said, the exhausted class would resolve to see that this did not happen again. “When those [lead-swingers] returned to their bunks,” reported Elden, “they’d have thirty to forty men mad at them, and they’d come back next time and do everything.”

Occasionally more extreme disciplinary measures were required. Noted Elden: “We had guys who were swinging the lead that even the Colonel couldn’t do anything with. So, Colonel White used to bring them to us, to give them a boxing lesson, with the Colonel usually looking on. Elden, a boxer, was in great physical shape, winning most of his fights. Said he of his boxing lessons to such fellows: “I’d tell them to hold their hands up like this,” said Elden, gesturing, “to guard their face against a blow, and while they were looking at me, I’d punch them in the nose. I’d tell them again to hold their hands up in front of their face, and while they were looking, I’d punch them again.” It might take a couple of lessons, said Elden, “but after that they’d cooperate. They all knew exactly what was happening! It was a way of getting to them where it was all legal.”

Because he was stationed so close to London, Elden spent his free time in and about that city. Yet he observed that as one’s time in London increased, and German raids on the city were reduced to mostly nuisance bombing, it got easy to become casual as to the hazards there. In that regard, he related two unnerving experiences.

One night, while staying at a hostel on the nearby Thames, Elden heard the ack-ack open up, some distance away in Hyde Park. “I was lying on my bed,” he said, “and I didn’t think it was necessary to go to the shelter. But as the bombs got closer and the noise got louder, sweat started to bead on my forehead.” Elden quickly got out of there then cautiously watched the bombing and searchlight activity “from behind a big marble pillar,” hoping it might provide him with some measure of safety. Fortunately, he never had to find out.

Another time, Elden was asleep in London when, “all of a sudden,” he said, “I found myself awake, sitting upright, bouncing on my bed.” He would later realize that he had actually heard the boom and felt the blast of an exploding V2 bomb before hearing the trailing sssh of the rocket that had carried it in. Acknowledged Elden; “The rocket beat its own sound.”

Elden Coleman was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who entered the Service during World War II. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage and persistence amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Swinging the Lead

P/T Instructor

Elden Coleman was a physical training (P/T) instructor in the Royal Canadian Army. On base at Cove, west of Farnborough, England, he and five other instructors worked their men hard amidst extensive training facilities that included two full gymnasiums. The main idea, said Elden, centred on keeping the fellows fit for combat. “We put ‘em in shape to go into battle,” he said, “and the demands of battle were supposed to be rigorous enough to keep them in shape.” Enlisted men were encouraged to participate in extra-curricular activities like basketball, football, track and field.

But P/T provided another valuable service—a form of discipline—to deter those fellows who were just “swinging the lead,” that is, not wanting to fully participate in physical exercises.

According to Elden, a typical P/T class involved hard training for fifty minutes out of an hour, with a ten-minute break before moving on to the next class. The fatigued men looked forward to the break. But in a group of thirty to forty men, he said, “you might have two or three guys who did not want to do anything, who were just swinging the lead.” As a punishment, Elden would announce that the whole class was going to continue exercising for the full hour, that there would be no ten-minute break before their next training session.

By the end of such a prolonged workout, he said, the exhausted class would resolve to see that this did not happen again. “When those [lead-swingers] returned to their bunks,” reported Elden, “they’d have thirty to forty men mad at them, and they’d come back next time and do everything.”

Occasionally more extreme disciplinary measures were required. Noted Elden: “We had guys who were swinging the lead that even the Colonel couldn’t do anything with. So, Colonel White used to bring them to us, to give them a boxing lesson, with the Colonel usually looking on. Elden, a boxer, was in great physical shape, winning most of his fights. Said he of his boxing lessons to such fellows: “I’d tell them to hold their hands up like this,” said Elden, gesturing, “to guard their face against a blow, and while they were looking at me, I’d punch them in the nose. I’d tell them again to hold their hands up in front of their face, and while they were looking, I’d punch them again.” It might take a couple of lessons, said Elden, “but after that they’d cooperate. They all knew exactly what was happening! It was a way of getting to them where it was all legal.”

Because he was stationed so close to London, Elden spent his free time in and about that city. Yet he observed that as one’s time in London increased, and German raids on the city were reduced to mostly nuisance bombing, it got easy to become casual as to the hazards there. In that regard, he related two unnerving experiences.

One night, while staying at a hostel on the nearby Thames, Elden heard the ack-ack open up, some distance away in Hyde Park. “I was lying on my bed,” he said, “and I didn’t think it was necessary to go to the shelter. But as the bombs got closer and the noise got louder, sweat started to bead on my forehead.” Elden quickly got out of there then cautiously watched the bombing and searchlight activity “from behind a big marble pillar,” hoping it might provide him with some measure of safety. Fortunately, he never had to find out.

Another time, Elden was asleep in London when, “all of a sudden,” he said, “I found myself awake, sitting upright, bouncing on my bed.” He would later realize that he had actually heard the boom and felt the blast of an exploding V2 bomb before hearing the trailing sssh of the rocket that had carried it in. Acknowledged Elden; “The rocket beat its own sound.”

Elden Coleman was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who entered the Service during World War II. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage and persistence amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Derald Miller

Anson Trainee

Drifting Backwards

Derald Miller of Magrath was trained at Fort Macleod, Alberta in a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where they flew the twin engine Anson aircraft. At nearby Lethbridge, students in the Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) flew the lighter Tiger Moth. Both locations were equally windy places.

A friendly rivalry existed between the Lethbridge and Fort Macleod stations as to who had the worst wind—each saying it was the other. The Lethbridge men claimed that a dog in Fort Macleod was blown up against a hangar there, where the wind blew so fiercely and long that before the dog managed to escape—it starved to death!

Indeed, the wind might blow very fiercely in the Lethbridge and Fort Macleod areas. Said Derald of his training there, “we could actually generate a negative ground speed while flying at seventy mph into a west wind.” That meant that with westerly gusts of up to eighty mph, a plane flying straight into the wind might, in theory, slowly drift backward and never get to its destination.

Derald Miller and all those who served in the military deserve our admiration. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Anson Trainee

Drifting Backwards

Derald Miller of Magrath was trained at Fort Macleod, Alberta in a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where they flew the twin engine Anson aircraft. At nearby Lethbridge, students in the Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) flew the lighter Tiger Moth. Both locations were equally windy places.

A friendly rivalry existed between the Lethbridge and Fort Macleod stations as to who had the worst wind—each saying it was the other. The Lethbridge men claimed that a dog in Fort Macleod was blown up against a hangar there, where the wind blew so fiercely and long that before the dog managed to escape—it starved to death!

Indeed, the wind might blow very fiercely in the Lethbridge and Fort Macleod areas. Said Derald of his training there, “we could actually generate a negative ground speed while flying at seventy mph into a west wind.” That meant that with westerly gusts of up to eighty mph, a plane flying straight into the wind might, in theory, slowly drift backward and never get to its destination.

Derald Miller and all those who served in the military deserve our admiration. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Stan Hoare

Killer Vaccinations

One Man Dead

10 Nov 2020

Stan Hoare (later of Magrath) and eight other fellows were rushed through a series of vaccinations in just a few days, to get them ready for priority service with the RAF in the Far East. In the process, said Stan, “my arm just felt like a pin cushion.” The vaccinations, of themselves, often resulted in cold and fever symptoms with the recipient at first feeling cold and clammy, then hot and hurtful. The next morning might find him confined to barracks with a fever.

Some men were more severely affected than others. In Stan’s case, the hurry to get the men through their shots had its price, when two of them were hospitalized and another one died. One veteran remembered the needles in the early stages of training in the Air Force, as being “the same size they used to vaccinate horses and cows!”

Stan Hoare was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such women and men did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Killer Vaccinations

One Man Dead

10 Nov 2020

Stan Hoare (later of Magrath) and eight other fellows were rushed through a series of vaccinations in just a few days, to get them ready for priority service with the RAF in the Far East. In the process, said Stan, “my arm just felt like a pin cushion.” The vaccinations, of themselves, often resulted in cold and fever symptoms with the recipient at first feeling cold and clammy, then hot and hurtful. The next morning might find him confined to barracks with a fever.

Some men were more severely affected than others. In Stan’s case, the hurry to get the men through their shots had its price, when two of them were hospitalized and another one died. One veteran remembered the needles in the early stages of training in the Air Force, as being “the same size they used to vaccinate horses and cows!”

Stan Hoare was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such women and men did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Don Harker

Move up... haul supplies

Italy Campaign

Don Harker was a driving instructor and truck driver in the Army Service Corps. When he crossed the Atlantic in May 1941, Don was assigned to stand Fire Watch, a specific kind of deck patrol. Because a cigarette could be spotted from far at sea, no one was permitted to smoke on deck. So when an officer lit a smoke, Don told him to put it out. “He told me to mind my own business,” said Don. In a few moments, Don’s superior officer arrived and told the fellow to put out the cigarette or he would be thrown overboard. And, said Don, “It was no idle threat!” So the cigarette got dropped over the side.

In July 1943, Don sailed from England for the Mediterranean to take part in the invasion of Sicily, landing the night after the first wave of assault troops had gone ashore. The next day his unit began trucking supplies ahead to the troops. Their route lay through a tortuous mountain pass that they had to daily traverse, “going up the mountain [loaded] at night with no lights while the Germans tried to destroy the trucks, then returning in the daylight, empty.” This went on for twenty-eight days until the enemy were driven out.

From Sicily, Don moved onto the Italian mainland where, he said, “The army would move up the line and we’d haul supplies—move up, haul supplies.” The Germans had a stronghold in the mountains at Monte Casino, near Monastery Hill, where they had kept the Americans pinned down for months. According to Don, the First Canadian Armoured Brigade was brought in, attached to the British Eighth Army, under General Montgomery. Don’s unit spent a few weeks hauling in ammunition for the artillery, whereupon he claimed, “Forty-eight hours after the first shot was fired, we were over the mountain.”

When he had first crossed the Atlantic, Don rode aboard a luxury liner, lodged in a comfortable state room having its own bath. At the end of the war, accommodations aboard troop ships had deteriorated considerably—the only sleeping arrangements available being hammocks.

Don Harker was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Move up... haul supplies

Italy Campaign

Don Harker was a driving instructor and truck driver in the Army Service Corps. When he crossed the Atlantic in May 1941, Don was assigned to stand Fire Watch, a specific kind of deck patrol. Because a cigarette could be spotted from far at sea, no one was permitted to smoke on deck. So when an officer lit a smoke, Don told him to put it out. “He told me to mind my own business,” said Don. In a few moments, Don’s superior officer arrived and told the fellow to put out the cigarette or he would be thrown overboard. And, said Don, “It was no idle threat!” So the cigarette got dropped over the side.

In July 1943, Don sailed from England for the Mediterranean to take part in the invasion of Sicily, landing the night after the first wave of assault troops had gone ashore. The next day his unit began trucking supplies ahead to the troops. Their route lay through a tortuous mountain pass that they had to daily traverse, “going up the mountain [loaded] at night with no lights while the Germans tried to destroy the trucks, then returning in the daylight, empty.” This went on for twenty-eight days until the enemy were driven out.

From Sicily, Don moved onto the Italian mainland where, he said, “The army would move up the line and we’d haul supplies—move up, haul supplies.” The Germans had a stronghold in the mountains at Monte Casino, near Monastery Hill, where they had kept the Americans pinned down for months. According to Don, the First Canadian Armoured Brigade was brought in, attached to the British Eighth Army, under General Montgomery. Don’s unit spent a few weeks hauling in ammunition for the artillery, whereupon he claimed, “Forty-eight hours after the first shot was fired, we were over the mountain.”

When he had first crossed the Atlantic, Don rode aboard a luxury liner, lodged in a comfortable state room having its own bath. At the end of the war, accommodations aboard troop ships had deteriorated considerably—the only sleeping arrangements available being hammocks.

Don Harker was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Blair M. Harker

Nightfighter Pilot

Missing in Action

Blair M. Harker joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in June of 1941. After two months in Manitoba in what the Army might have called Boot Camp, and another six months of intensive training in Saskatchewan, he graduated as a Sergeant pilot. Blair hoped to receive the King’s Commission, becoming an officer, but he missed that cut by one point in 1700.

In March 1942, Blair crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a convoy of merchant ships carrying troops and supplies. It was the worst possible month of the war to do so. In terms of Allied shipping losses, 95 vessels were sunk, with over 40% of these being torpedoed—and not a single submarine destroyed. He arrived safely, travelling aboard a fast ship, the Capetown Castle.

In England, a light amidst the uncertainty of military life was his meeting Marjorie and their forging a love that would last beyond the grave. Increasingly, Blair found himself following a night training schedule, often flying after 10 PM, frequently after midnight.

During nightfighter training in Scotland, he crewed-up with his navigator, V.I. (Willie) Williams. But the station’s compliment of Beaufighters—the aircraft he would soon fly into combat—was indeed very lean. It was a full month before he got into a Beau and three weeks after that before he flew one alone. Such war-weary aircraft could be decidedly unsafe! While flying, one of Blair’s engines took fire and by the time he and Willie made base, their hydraulics were gone. Without the aid of braking flaps, they hit the tarmac at 180mph, “running off the runway, through a fence and over a ditch.”

Posted to active combat in November 1942, Blair flew his newer Beaufighter in 409 RCAF Squadron, out of Coleby Grange in Lincolnshire. The Squadron Motto, Media Nox Merides Noster, stood for Midnight is Our Noon. He was assigned to ‘B’ Flight, that portion of the ground and aircrew responsible for roughly half the squadron’s 13 aircraft.

Blair was eventually scheduled to be the first off in attempting to intercept enemy bombers. “If any Jerries come around here,” he vowed, “too bad for them.” But the flying was scrubbed due to bad weather. It would be two months later before he and Willie got into one of their few probable tangles with the enemy but, “due to poor Ground Control,” complained Blair,” I could not locate him at all.” He and Willie’s effort counted as one of only two or three near intercepts by 409 Squadron that month.

Another time, when Blair and Willie were coming in from an evening of cross-country flying, Control called up to say that a raid was coming on. “He put me up to 10,000 feet and onto a bogey,” said Blair. “I found him okay, but it took me quite a while to find what he was.” Little wonder, for the bogey was a Ju 88, an enemy aircraft often mistaken for a fellow Beaufighter. By the time Blair identified the bandit, the enemy realized that he was being stalked. “The Jerry saw me at the same time as I found out what it was,” said Blair, “and... I only got a couple of shots in at him.”

One day, he reported in alarm, “My port motor cut out on me, blew a cylinder out and the cowling part way off!” Bair and Williams had been practicing air-to-sea firing and were coming in across the coast when the disaster occurred. Blair required all his single-engine flying skills to make a forced landing at an aerodrome still under construction—amidst piles of sand, drainage pipes and other hazards. A letter followed shortly, complimenting him on the landing.

In February of 1943, Blair was given the highly dangerous assignment to fly night Intruder missions into occupied France. Such a ground-strafing sortie was a most intimidating prospect. The intent was to harass the enemy, then beat a hasty retreat for home. It sounded great in theory but could be disastrous in practice. In Blair’s case, it was.

On the night of April 16, when flying out of Middle Wallop in southern England, Blair narrowly escaped from his first Intruder sortie. On his way out of France, after having successfully shot up a couple of locomotives in a railroad junction, he inadvertently flew directly over a flak ship—and the flak found its mark. “They hit the starboard wing…” said Blair, “the right tire… and propeller blade.” His aircraft was now seriously damaged, and he later made what the Squadron Diarist described as “a wizard landing….”

Two days later, with his own aircraft still in for repair, Blair was given a new route to fly, taking off at 2200 hours. He had spent the previous night in London with Marjorie and all those there who were dearest to him. But he was never heard from again. His navigator’s body was eventually recovered on the coast of France. But Blair, having no known grave, has his name inscribed along with 20,000 other missing Commonwealth fliers at the Runnymede War Memorial in England.

Blair Harker was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Nightfighter Pilot

Missing in Action

Blair M. Harker joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in June of 1941. After two months in Manitoba in what the Army might have called Boot Camp, and another six months of intensive training in Saskatchewan, he graduated as a Sergeant pilot. Blair hoped to receive the King’s Commission, becoming an officer, but he missed that cut by one point in 1700.

In March 1942, Blair crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a convoy of merchant ships carrying troops and supplies. It was the worst possible month of the war to do so. In terms of Allied shipping losses, 95 vessels were sunk, with over 40% of these being torpedoed—and not a single submarine destroyed. He arrived safely, travelling aboard a fast ship, the Capetown Castle.

In England, a light amidst the uncertainty of military life was his meeting Marjorie and their forging a love that would last beyond the grave. Increasingly, Blair found himself following a night training schedule, often flying after 10 PM, frequently after midnight.

During nightfighter training in Scotland, he crewed-up with his navigator, V.I. (Willie) Williams. But the station’s compliment of Beaufighters—the aircraft he would soon fly into combat—was indeed very lean. It was a full month before he got into a Beau and three weeks after that before he flew one alone. Such war-weary aircraft could be decidedly unsafe! While flying, one of Blair’s engines took fire and by the time he and Willie made base, their hydraulics were gone. Without the aid of braking flaps, they hit the tarmac at 180mph, “running off the runway, through a fence and over a ditch.”

Posted to active combat in November 1942, Blair flew his newer Beaufighter in 409 RCAF Squadron, out of Coleby Grange in Lincolnshire. The Squadron Motto, Media Nox Merides Noster, stood for Midnight is Our Noon. He was assigned to ‘B’ Flight, that portion of the ground and aircrew responsible for roughly half the squadron’s 13 aircraft.

Blair was eventually scheduled to be the first off in attempting to intercept enemy bombers. “If any Jerries come around here,” he vowed, “too bad for them.” But the flying was scrubbed due to bad weather. It would be two months later before he and Willie got into one of their few probable tangles with the enemy but, “due to poor Ground Control,” complained Blair,” I could not locate him at all.” He and Willie’s effort counted as one of only two or three near intercepts by 409 Squadron that month.

Another time, when Blair and Willie were coming in from an evening of cross-country flying, Control called up to say that a raid was coming on. “He put me up to 10,000 feet and onto a bogey,” said Blair. “I found him okay, but it took me quite a while to find what he was.” Little wonder, for the bogey was a Ju 88, an enemy aircraft often mistaken for a fellow Beaufighter. By the time Blair identified the bandit, the enemy realized that he was being stalked. “The Jerry saw me at the same time as I found out what it was,” said Blair, “and... I only got a couple of shots in at him.”

One day, he reported in alarm, “My port motor cut out on me, blew a cylinder out and the cowling part way off!” Bair and Williams had been practicing air-to-sea firing and were coming in across the coast when the disaster occurred. Blair required all his single-engine flying skills to make a forced landing at an aerodrome still under construction—amidst piles of sand, drainage pipes and other hazards. A letter followed shortly, complimenting him on the landing.

In February of 1943, Blair was given the highly dangerous assignment to fly night Intruder missions into occupied France. Such a ground-strafing sortie was a most intimidating prospect. The intent was to harass the enemy, then beat a hasty retreat for home. It sounded great in theory but could be disastrous in practice. In Blair’s case, it was.

On the night of April 16, when flying out of Middle Wallop in southern England, Blair narrowly escaped from his first Intruder sortie. On his way out of France, after having successfully shot up a couple of locomotives in a railroad junction, he inadvertently flew directly over a flak ship—and the flak found its mark. “They hit the starboard wing…” said Blair, “the right tire… and propeller blade.” His aircraft was now seriously damaged, and he later made what the Squadron Diarist described as “a wizard landing….”

Two days later, with his own aircraft still in for repair, Blair was given a new route to fly, taking off at 2200 hours. He had spent the previous night in London with Marjorie and all those there who were dearest to him. But he was never heard from again. His navigator’s body was eventually recovered on the coast of France. But Blair, having no known grave, has his name inscribed along with 20,000 other missing Commonwealth fliers at the Runnymede War Memorial in England.

Blair Harker was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Ken Gibb

Safe at Home

Piloting in Canada

Ken Gibb joined the RCAF, hoping to become a Wireless-operator/Air gunner (WAG). Recently married, in early 1941 he was ordered to report to the Air Force in three weeks time. According to his wife, Ila Zemp, at 5ft 7in tall, Ken was thin and active, a quiet gentle person who, she said, “had a great sense of humour and a quick comeback to any remark.” It was fun having Ken around.

But fairly soon during his early training experiences, Ken got transitioned from his plans of becoming a WAG, to that of being a pilot. He took much of his training in the province next door, getting his pilot’s wings in Yorkton, Saskatchewan.

Ken went on to fly twin-engine Anson aircraft in New Brunswick, ferrying navigator and bombardier trainees across the skies. There, amidst the security of remaining in Canada, he earned about $250 - $300 a month, while his friends flying combat missions in England collected less than half that amount. Still, no one held the pay discrepancy against Ken personally. That was just the lack of logic one expected in a war.

Ken Gibb was no glory-seeking war hero, nor were the majority of those who served in the military. Theirs is a compelling tale of the times, of courage amidst adversity. What such men and women did is a testimony to their integrity and a blessing upon our heads.

Safe at Home

Piloting in Canada

Ken Gibb joined the RCAF, hoping to become a Wireless-operator/Air gunner (WAG). Recently married, in early 1941 he was ordered to report to the Air Force in three weeks time. According to his wife, Ila Zemp, at 5ft 7in tall, Ken was thin and active, a quiet gentle person who, she said, “had a great sense of humour and a quick comeback to any remark.” It was fun having Ken around.

But fairly soon during his early training experiences, Ken got transitioned from his plans of becoming a WAG, to that of being a pilot. He took much of his training in the province next door, getting his pilot’s wings in Yorkton, Saskatchewan.